To be hidden in God, known only by Him is a great treasure, which today’s saint, the Franciscan Joseph of Cupertino, lived to the full. Amare nesciri, Saint Philip Neri would say, ‘love to be unknown’. With his father’s death while Joseph was still in utero, the Italian boy, whose hometown was on the ‘heel’ of the boot of Italy, had a difficult upbringing, often abused and neglected. But from childhood, Joseph, by the grace of God, maintained a joyful disposition, gifted with ecstatic visions. He was so rapt in the love of God that he would suddenly fall motionless while drying a dish or hoeing a field, a beatific smile on his face, mouth agape, imperturbable, always cheerful, practising a rather severe asceticism which flowed from the deep well of his charity.

He was generally seen as ‘useless’, but, after a number of rejections, was finally accepted into the Franciscans in 1620. He would obey his superiors and the rule without a moment’s hesitation, always seeing Christ or Our Lady in each person he met. It was almost as though holiness came naturally to him. His continued prayer and ecstasies made study difficult, but he passed the examination for the diaconate, as the Bishop examiner asked the one Scripture passage on which he could discourse with ease (hence, he is the patron saint of exam-takers, students take note!). Ordained in 1628 (again, after an apparently miraculous examination) Friar Joseph’s devotion increased, and, paradoxically, he soon had to be secluded, for there were so many eyewitness accounts of him levitating, absorbed in God (as was recorded of other saints, such as Thomas Aquinas, a man whose build would defy easy hovering). Modern sceptics try to claim that Joseph was actually ‘leaping around’ like some gymnast from Circque de Soleil, but the monks and townspeople would see the friar of Cupertino quite literally fly (he is also the patron saint of aviators). At one point, while in the presence of Pope Urban VIII (the one embroiled in the Galileo fiasco, but who also sent the Jesuit missionaries to Canada), Joseph hovered upwards in a fit of devotion for the Vicar of Christ, and only came back to earth at the direct order of his superior. The spectacle became such that the Franciscans eventually placed him in a solitary cell, away from any public events or community prayer, a ‘being alone with God’ which Friar Joseph did not mind all that much, so long as he could continue to say Mass.

Joseph was eventually permitted back into conventual life in 1657, and died on this day 1663.

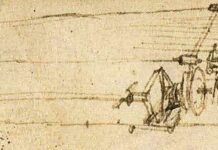

A few decades after Friar Joseph’s heavenly aviation, without guy-wires and ropes, Newton formulated his laws of physics, published in 1687 in his great Principia Mathematica, introducing the mechanistic model of the universe, one governed by immutable laws, which every schoolboy now learns (at least, I think they still do).

Yet are they? The laws immutable, I mean? Einstein discovered three hundred years after Newton that time and space are not quite what they seem to be. And, more to our point, in today’s Gospel, Christ raises a young man from the dead, and He Himself ascended before the eyes of the Apostles into heaven, both apparently ‘impossible’. But with God, all things…

We should remember that, in reality, heaven is not ‘up there’, nor ‘far away’, but rather all around us, with eternity and time intermingling, the former sometimes bursting forth into the latter, with the remarkable results that we call ‘miracles’.

The ‘great’ ones of the world may never have heard of Saint Joseph of Cupertino, and most don’t believe in miracles, which is too bad. For, really, as Chesterton points out in his ‘Logic of Elfland’, is not the entirety of creation a miracle, that trees produce bright red delicious apples, and water clear and refreshing? Our narrow materialistic age might see things more clearly, or perhaps more broadly, if we could see ourselves and everything around us, as the saint of Cupertino did, sub specie aternitatis, under the aspect of eternity. Only then do things make sense; and only then will everything that transpires in this passing world, at some deep and abiding level, make us truly joyful.

As Chesterton also once quipped, the angels can fly because they take themselves so lightly. Would that we could, with the happy Friar, see heaven all around us, however dim and obscured by the sin around us. For Christ has already overcome the world, and His arrival will reveal what we should, and could, have seen all along.