Long ago, there was a surefire test by which to recognize a truly cultured person: anyone who could hear the William Tell overture without thinking of the Lone Ranger. One’s reaction to the word “mediaeval” is a similar sort of test for Catholics. You fail if “mediaeval” has for you connotations of ignorance and bigotry. Eric Hoffer, whose book The True Believer was popular a few yeas ago, expressed very well the mindless popular conception of the Middle Ages when he referred matter-of-factly to “the stagnation of the Middle Ages” or to “Stalin’s medieval mind.” Similar is his description of Hitler’s destruction of the Jews: “When the Middle Ages returned for a brief decade in our day, they caught the Jew without his ancient defenses and crushed him.”

Now one thing Stalin and Hitler were not is mediaeval. The Middle Ages brought unsuitable rulers in sackcloth to Canterbury or barefoot in the snow to Canossa. I wish it were possible to imagine a barefoot Stalin doing penance in the Gulag or Hitler in sackcloth and ashes being flogged at Auschwitz. That these images are incongruous is a good indication of one difference between our time and the mediaeval: it is a matter of scale. One feels that Hitler and Stalin killed a greater number of people than were ever alive at any one time during the entire Middle Ages. A sophisticated technology of mass murder is a modern invention. Another difference is our bureaucratic approach to genocide. It is an evil that seems to have no primary agent; there are only faceless functionaries. Whatever such atrocities may be, they are certainly not mediaeval. Mediaeval man was imbued with a sense of the presence of God. He looked on creation as revelatory of God’s majesty and the moral order, and he found in the Church the presence of Christ and the assurance of salvation.

It will be clear to anyone reading this editorial that I pass the second test with colours flying (to use a mediaeval image). I do so partly because I have an antiquarian streak, but mainly because I learned from earliest childhood to admire the institutions and achievements of the Middle Ages, and nothing I have read or experienced since then has led me to question the accuracy of what I was taught. The art of the Middle Ages will be good indication of their greatness; for surely, it is art more than anything else that allows us to assess a civilization. Hitler and Stalin were the patrons of an ugly, gargantuan art that is universally disdained, but people will take as simple a thing as a page from a mediaeval book and frame it.

For most of us, the great Gothic cathedrals represent the pinnacle of mediaeval art. They are supreme achievements incorporating many forms of art into a single harmonious whole which one wants to call an event rather than a building:

Christ prophesied the whole of Gothic architecture in that hour when nervous and respectable people . . . objected to the shouting of the gutter-snipes of Jerusalem. He said, “If these were silent, the very stones would cry out.” Under the impulse of his spirit arose like a clamorous chorus the facades of the mediaeval cathedrals, thronged with shouting faces and open mouths. The prophecy has fulfilled itself: the very stones cry out.

G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

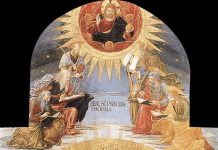

With its buttresses flying, the Gothic cathedral has the look of a fantastic beast about to gallop off across the fields. I don’t think that this is entirely unintended, for when one examines mediaeval art one discovers that no small part of its attraction is a sense of whimsy. “The Mystic Mill” a small sculpture at the top of a column in the church of Saint Mary Magdalene in Veselay, France, (pictured below) is a good example. The carving shows one of the prophets pouring into a mill the Old Testament in the form of grain which Saint Paul collects transformed into the flour of the New Testament. Everything in the cathedral, from this tiny piece of sculpture to the cruciform foundation, becomes part of the whole by portraying some aspect of the history of salvation, from creation to the general judgment. Angels and saints are present in the art because the full body of Christ, head and members, are united in the divine liturgy of heaven and sacramentally made present in the ceremonies celebrated in this sacred place.

Mediaeval art proclaims God’s fidelity to his people. The humblest Christian is ennobled by the holy things God gives him in Christ. Man’s actions are significant and his self-worth is assured by the dignity and splendour of his worship. It is hard for us to share the mediaeval optimism about the human condition. Perhaps it is because we have seen too many Hitler’s and Stalin’s. For whatever reason, the contemporary Church has in many ways put aside its mediaeval heritage. But when faith is renewed and hope is restored we shall again discover the religious optimism inherent in the Catholicism of every age.