(New contributor Mary Innerst offers here a reflection of the beauty of her time studying at the ITI – the International Theological Institute – in Trumau, Austria, where I spent a delightful few days last summer. Our own liberal arts college, Our Lady Seat of Wisdom, here in the scenic Madawaska Valley, shares a transfer agreement with the ITI, as a sister institution engaged in the vital work of educating future generations in the truth. A recent article points out that it’s only the faithful and orthodox colleges that are growing. As Pope John Paul II put it, the “Catholic University is without any doubt one of the best instruments that the Church offers to our age which is searching for certainty and wisdom”) Ed.

Facts are to be possessed and used. This was the understanding I held implicitly throughout a secular secondary education and into the first two years of community college. “Knowledge” was a conglomeration of strange things somewhere outside of me; if I was fortunate, they would cling superficially to me for a time. Truth was a cumbersome, awkwardly-shaped reality that I had to force myself to bear. Each fact, which I considered someone else’s, had to be grasped as an alien object in my mind; I exhausted myself by tenaciously holding each of them , terrified of letting any slip through the sieve of my straining mind. It was like trying to cup water in my hands—as soon as I received them, they would already be leaking out and dripping into forgetfulness. Some of my professors denied any objective truths entirely, professing their truth, which made grasping and applying what they taught all the more difficult. I was juggling shadows; my only experience was what Dorothy Sayers describes in The Lost Tools of Learning, her account of the modern pragmatist’s error in his approach to learning:

We have merely a set of complicated jigs, each of which will do but one task and no more… so that no man ever sees the work as a whole…They learn everything, except the art of learning.[1]

In short, what I learned was not connatural to me. It felt forced and foreign. It felt like a burden. I loved education for what I could do with it, for what I could get from it, but in the time before I arrived at ITI (International Theological Institute) Catholic University to study the Liberal Arts I never loved it for its own sake. Upon arriving in Trumau, Austria, I was quickly introduced to the benefits of the direct approach to primary sources and the importance of not relying on secondary accounts to substitute for first principles. As our professor and university president was so keen to remind us, if one reads the original, “you cannot be lied to.” Intrigued by the prospect of this medieval approach to learning, I drew close to the first font, logical first principles and the arguments to be derived therefrom, and dove face-first into the sources set before me.

I walked the halls of history, armed with assertions from primary sources. I internalized them, but in doing so encountered an objection, which in turn was answered by someone thinking with me hundreds, if not thousands of years ago, whose thoughts fit like a puzzle piece into my own thought, contributing to the picture that was forming. We were led on these excursions by professors as guides, like Virgil leading Dante through the purgative realm to glimpse something of the eternal stars of virtue beyond. On and on it went, in each subject, until they began to converge, and I realized: all these arguments are in fact, just one. I could, without any fear of losing my footing, step back and survey the expansive horizon opening before me.

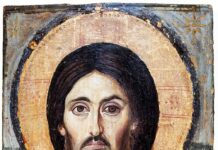

As I gradually learned to use the tools of learning, the mysterious formulation of Psalm 42 became an increasingly familiar experience to me: “deep is calling to deep.”[2] Something primeval, something deeper than my deepest self, shifted; a mysterious transformation was taking place. It was as though I had discovered a new dimension within myself, a deep-seated identity with what I was reading. I had failed, all those years, to recognize the transcendently penetrating nature of knowledge. It is, in a mysterious way, part of me—permeating to the depths—and yet utterly beyond me. I was shocked to be confronted, not by a finite reality, but something infinite. I stared into the face of my Creator. St. Augustine addresses God in the midst of such an intimate encounter: “You were more inward to me than my most inward part and higher than my highest”.[3] It was here that I found myself approaching a second source, a deeper and sweeter source, a font that the Liberal Arts prepares us for and points to: the supernatural spring of Divine Wisdom itself.

It is here that I discovered a marvelous phenomenon: the human intellect, when it operates according to its proper function, unfailingly leads to God, the First Cause. What do we do when we reach the limit of logical arguments, the outer limits of our natural faculties? We jump into the arms of faith. The setting for this leap of mine was ITI, as I graduated to the Master’s program in Sacred Theology, building on the solid foundation of the Liberal Arts. It became the meeting place for two aspects crucial for human flourishing, namely, intellectual and spiritual rigor. My days looked something as follows: I left class and jumped directly into the arms of the Church’s sacramental life, comprised of Eastern and Western rites, breathing with both lungs. What I had just learned took supernatural root in my soul. I’ve gained an especially deep appreciation of the Eucharist, in which we are privileged to receive the real body of the very Truth Himself. I returned to class, and the sources were illuminated by the liturgy just celebrated and, in turn, supported my next experience in prayer. And so, the living cycle continued.

I spent five years partaking of these two fonts, “as a deer that longs for running streams,”[4] one natural and the other supernatural. Such a double-contact is transformative—it sweeps the entire person, body, soul, and spirit, into one grand reditus in the very process of revealing his exitus. Education is not just a question of pure empirical knowledge, but a matter of anthropology. The human heart beats out the questions, What am I? Who am I? Who am I for? and stirs impatiently with the restlessness St. Augustine describes as only quieting when the heart rests in her identity in God. Knowing from Whom you came and to Whom you are going tells you what you are and how to act according to your nature. This is freedom. This is the “liberality” implied in the very name “Liberal Arts.”

Everything I learned in this process toward true freedom—yes, even all those seemly disconnected facts that so troubled my earlier educational efforts—points to Christ, the Logos, Who, in turn, reveals something to me about myself. As Pope Benedict XVI observed so beautifully: “Jesus Christ is the personified Truth…Every other truth is a fragment of the Truth that he is and refers to Him.”[5] Learning is no longer a game of grasping at foreign objects with a utilitarian aim, but a living experience of coming to know myself and creation in relation to the Last End, as I strive to conform myself to Truth personified. “It is not I who live, but Christ who lives in me”.[6] Isn’t this, after all, the ultimate goal of knowing anything? This is proper human education, an education which, in Sayer’s words, “looks to the end of the work,”[7] namely, to know and love God for all eternity.

Endnotes:

[1] Dorothy Sayers, The Lost Tools of Learning (ET Heron Publishing, 1948), 6.

[2] Psalm 42:7

[3] St. Augustine, Confessions, ed. And trans. Albert C Oulter, PhD, DD, 3.6.11.

[4] Psalm 42:1

[5] Pope Benedict XVI, “Address of His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI to the Participants in the Plenary Assembly of the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith,” (2006).

[6] Galatians 2:20

[7] Sayers, 20.