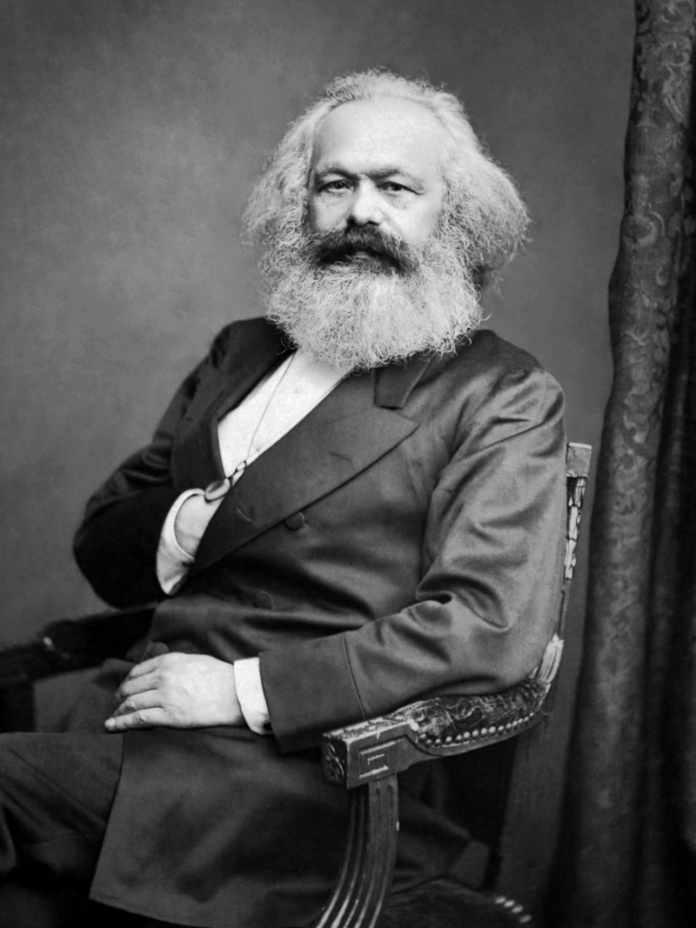

Recently, as I rarely do these days, I engaged in a social media exchange in response to a post by a political commentator and intellectual who goes by the name of Dorothy Lennon. That exchange inspired this essay. Lennon, who, more often than not, provides pointed and thoughtful critiques of oligarchic corruption, endless global wars, and the troubling development of worldwide surveillance, shared a widely circulated anecdote about Karl Marx’s personal poverty while writing Capital: “A week ago I reached the pleasant point where I am unable to go out for want of the coats I have in pawn, and can no longer eat meat for want of credit.”

Even though I prefer to avoid online “debates,” because of their futility and time consumption, I occasionally engage, simply because throughout my life I have witnessed how planting seeds of truth can come to have profound spiritual effects in people’s lives.

She mentioned this as a testament to Marx’s character, suggesting that he was motivated not by fame or profit but by a sincere desire to empower the working class and create a better world. But this kind of narrative commits a common fallacy. It confuses personal hardship with moral or philosophical virtue. Many destructive or even evil figures have suffered for their ideas. For example, Adolf Hitler endured imprisonment while writing Mein Kampf. Vladimir Lenin spent years in exile before launching the Russian Revolution. Thus, suffering for an ideology does not automatically vindicate it. The real question is not whether Marx was sincere, but whether he was right.

Marx’s philosophy, though often disguised as concern for the poor, is riddled with problems, both anthropological and economic. First, it expounds a reductionist understanding of the human person. It reduces human persons into pawns of class warfare, not in their proper nature as moral agents created in the image of God. Second, it denies the legitimacy and moral value of private property, failing to recognize how properly ordered ownership cultivates responsibility, stewardship, and social stability. Third, Marx portrays markets as systems of exploitation rather than recognizing them as spaces for voluntary exchange. Yet when grounded in ethical principles and guided by the principle of subsidiarity, markets have the proven capacity to lift entire populations out of poverty. Fourth, his economic theory depends on the widely discredited labour theory of value. This theory neglects to consider the significance of innovation, entrepreneurship, risk, and consumer demand in shaping actual value and driving economic expansion. Fifth, it replaces the decentralized knowledge and organic adaptability of free, morally grounded markets with the rigid structures of centralized planning, which has consistently led to stagnation, scarcity, and systemic corruption. But most detrimental is that Marx’s system severs the human being from his transcendent source. It denies the spiritual dimension of human persons, offering not true liberation but a hollow utopia that degrades souls, families, and societies.

Beneath the economic and political slogans lies a deeper pathology. Marx’s philosophical system is grounded in scientific materialism, class envy, and a categorical rejection of moral absolutes. Whether deliberately or not, his work paved the way for some of the most brutal regimes in modern history: Stalin’s gulags, Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward, and the Khmer Rouge’s killing fields under Pol Pot. Marxist ideology ultimately strips human beings of their inherent dignity, denying the imago Dei, the image of God, and reducing the person to a mere byproduct of class warfare. As Paul Kengor documents in The Devil and Karl Marx, Marx’s writings and poetry reveal a disturbing preoccupation with destruction, nihilism, and even Satanic motifs. This spiritual dimension of Marx’s thought, so often overlooked, casts a sinister light on the revolutionary fervour he helped ignite.

In one of her posts of President Trump’s 2025 inauguration, Lennon remarked on the visible unease among tech oligarchs such as Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, Sundar Pichai, and others whose collective wealth exceeds $1.35 trillion when references to God and Christ were made. That discomfort raises questions not only about their worldview but also about the deeper spiritual currents that underlie elite hostility to Christian truth. Many of these same elites actively promote ideologies such as Marxism, transhumanism, or hyper-materialism, which, like Marx’s own system, are antagonistic to God, objective morality, and human dignity. In this light, it is surprising, even given Lennon’s socialist sympathies, to see such uncritical admiration for Marx, whose legacy is so deeply entangled with both spiritual and political ruin.

While it is necessary to confront the real injustices of our time, whether they come in the form of neoliberal economic exploitation, predatory globalism, or the erosion of worker dignity by unaccountable technocrats, we must be discerning about the solutions we embrace. Exchanging one form of dehumanization for another is not moral progress but moral regression. Quite distinctly, Christianity calls us to a justice that is rooted in truth, ordered to love, and elevated by the dignity of the human person made in the image of God. Marxism, by contrast, offers a counterfeit salvation, one that demands vengeance rather than reconciliation and thrives on resentment rather than grace.

Dorothy Lennon’s otherwise incisive political analysis often overlooks the weaponization of Marxist ideology by oligarchs through media, academia, and government. Instead of liberating the working class, their aim is to divide and destabilize society for their personal benefit. With the collapse of classical economic Marxism, its modern reincarnation, often termed cultural Marxism, has flourished. The focus of the struggle has now shifted from ‘class’ to a wide range of identities, including race, sex, religion, and more. This ideological shift has proven useful to globalist elites who exploit such division to weaken national cohesion, erode religious and moral foundations, and increase dependence on centralized institutions. As a result, Marxism has become one of the most effective tools in the oligarchs’ arsenal, not for empowering the oppressed but for managing populations through confusion and control. As former KGB defector Yuri Bezmenov warned, this form of ideological subversion is not a path to justice but a strategy of demoralization, designed to fracture societies from within and render populations easier to control. As Michael Rectenwald and Rod Dreher have shown, Marxist language has been absorbed by technocratic and corporate elites not to dismantle power but to justify ever-expanding control. The great irony is that while Marxism once claimed to fight elite domination, it now serves as ideological cover for it. That this dynamic remains a major lacuna in Lennon’s political and moral vision is both surprising and revealing.

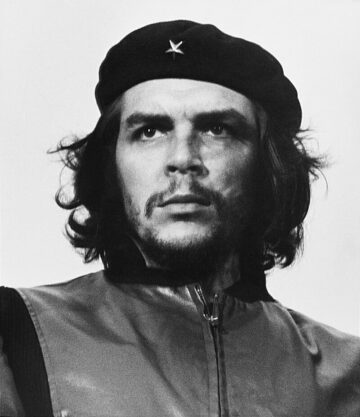

Che Guevara and the Death of Redemption

The conversation soon turned to Marx’s ideological descendant, Che Guevara. To some, Che remains a symbol of resistance, romanticized as a revolutionary hero. In my younger days, when pursuing undergraduate studies, I, too, glorified Che Guevara’s cause. I also attached a false affinity to him because of my Argentinian roots and Spanish heritage. But as I learned more about him and history, I quickly rejected what he embodied. This is particularly evident when examining some of his statements. His words disclose a deep contempt for Christian love, mercy, and self-sacrifice. In writing to his mother, he says:

“I am not Christ or a philanthropist, old lady. I am all the contrary of a Christ. I fight for the things I believe in, with all the weapons at my disposal and try to leave the other man dead so that I don’t get nailed to a cross or any other place” (Letter to his mother, July 15, 1956, as quoted in Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life by Jon Lee Anderson, 1997).

Even more disturbingly: “In fact, if Christ himself stood in my way, I, like Nietzsche, would not hesitate to squish him like a worm.” These are not the words of a misunderstood idealist. They represent a rejection of the Cross and a renunciation of the very heart of Christian morality. For Che, freedom was inseparable from bloodshed, not as a tragic cost but as a necessary engine of revolution. And yet, as I noted in that same exchange, Che got the martyrdom he so bitterly scorned. He died in a Bolivian jungle, executed and laid out for display like a failed messiah. History has a way of exposing the hollowness of its anti-saviours.

Revolution or Redemption?

This brings us to a more profound question. In the face of real-world injustices, such as the plight of Palestinians or the concentration of global power in the hands of unaccountable elites, what can truly liberate the oppressed? Is it violent revolution or Christian redemption?

Consider, for instance, Che’s tactics. Could they truly assist the Palestinian cause today, a concern that features prominently in Lennon’s writings? Israel’s heavy-handed military responses, including disproportionate force and collective punishment, have undeniably contributed to the suffering of Palestinians and inflamed tensions in the region. Yet D-grade weapons against tanks and drones only invite further death and despair, as seen in Hamas’s often self-defeating assaults. Vengeance cannot build a just society; it only deepens wounds and perpetuates hatred. In contrast, Christ offers a model of radical transformation, not through retaliation, but through redemption; not through domination, but through conversion. The Cross is not passive; it confronts evil head-on while never succumbing to it. It is only Christ who can break the cycle of bloodshed through the power of sacrificial love.

The Historicity of Christ

At a certain point, the online “debate” shifted from politics to ridicule of Christian belief. Some dismissed the Bible as “babble.” Others denied that Jesus ever existed. One user even quoted, or rather misquoted, the phrase “I am a man of one book,” attributing it to St. Thomas Aquinas, in an attempt to mock Christian reliance on Scripture. This exchange revealed not only a contempt for Christian faith but also a broader ignorance of argumentation, logic, philosophy of religion, and historical method, common among those who mistake mockery for reasoned discourse.

But that quote, Homo unius libri timeo, “I fear the man of a single book,” is frequently misunderstood and misattributed. It was popularized by Bishop Jeremy Taylor, who noted Aquinas’s respect for the mastery of one sole book or subject, and some have used it to diminish his thought. However, Aquinas read broadly, engaging deeply with Aristotle, Plato, Averroes, and Maimonides, among others, in demonstrating that faith and reason are not enemies but allies in the pursuit of truth.

Moreover, the denial of Jesus’s existence is not only unfounded. It is intellectually dishonest. The historical evidence for Jesus of Nazareth includes not only Christian writings but also multiple non-Christian sources. Among them:

- Tacitus, the Roman historian, documented that Pontius Pilate executed Christus, the founder of the Christian movement, during the reign of Tiberius.

- Josephus, a first-century Jewish historian, referred to Jesus in Antiquities of the Jews, where he noted His crucifixion and reported resurrection.

- Suetonius noted that followers of “Chrestus,” likely referring to Christ, caused disturbances among Jews in Rome.

- Pliny the Younger, a Roman governor, described Christians as worshipping Christ “as a god” and refusing to offer sacrifices to the emperor.

- Lucian of Samosata, a Greek satirist, ridiculed early Christians for their devotion to a crucified man and their readiness to sacrifice their lives for their convictions.

- Mara Bar-Serapion, a Syrian philosopher writing from prison, referred to the execution of a “wise king” of the Jews.

- The Babylonian Talmud refers to “Yeshu” being “hanged” (a euphemism for crucifixion) on the eve of Passover.

These sources, many of them skeptical or hostile to Christianity, nevertheless confirm key historical facts: Jesus lived, taught, gathered followers, and was crucified under Roman authority. To deny this is not skepticism. It is historical amnesia.

Author: Dianelos Georgoudis

(creative commons)

I invited commentators and skeptics alike to read my article, “Resurrecting Reason: A Rejoinder to Raphael Lataster on Miracles and the Rationality of Theism,” which addresses many false claims about the historicity of Jesus, the existence of God, and the rationality of belief. It addresses the philosophical and historical evidence for Jesus’ life, miracles, and resurrection and exposes the errors in common atheist critiques of Christianity.

The True Opium

Karl Marx infamously claimed that “religion is the opium of the people.” But history has shown otherwise. It is not Christianity that sedates the soul and blinds people to reality. It is Marxism that has become the opiate, numbing the minds of the godless, intoxicating tenured academics, and addicting those who have forgotten history’s warnings.

Marxism promises liberation but delivers tyranny. It replaces the Kingdom of God with the tyranny of men. Its saints are executioners. Its sacraments are blood and envy. Its heaven is an illusion.

Christianity, by contrast, is not a substance used to numb us from reality, but rather it is like a fire that purifies us. It calls us to self-denial, truth, and radical love. It does not pacify us but profoundly transforms us.

In a world disoriented by false gospels and exhausted by ideological extremes promulgated by delusional ideologues, the answer is not Marx. The answer is not Che. The answer is only Christ, the Way, the Truth and the Life.