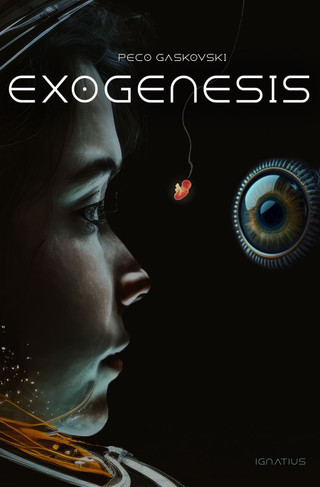

Exogenesis, by Peco Gaskovksi

Ignatius Press, 2023

ISBN/UPC: 9781621646341

One of the most difficult things in writing a ‘fantasy’ – any story which is not based on this present world – is constructing a realistic and believable ‘other world’. In his famous essay on Fairy Tales, J.R.R. Tolkien calls this a ‘sub-creation’, at which he was a master. Middle Earth is more real to some people than real Earth, replete with languages, customs, races, history, all of which make it very believable indeed.

In his own recent future dystopic fantasy, Peco Gaskovski does a remarkable job. The novel takes place in some indeterminate future (one which seems closer with each passing day), in which residents of Lantua, a vast city-state wherein citizens live under constant surveillance by cameras and ubiquitous drones, their behaviour controlled by a strict reward and caste system. The people are placated by various means – casual sex (almost everyone is sterilized), drugs, as well as psychophysiological neural stimulation. Children are born – if we may use that term – by ‘exogenesis’; that is, in artificial wombs, and hence the title. The unwanted embryos are ‘discarded’, but secretly, which plays a part in the plot. There’s more than a bit of Brave New World, and, tragically, now a hundred years after that original dystopia, our own IVF world.

Outside of the city-state, groups of primitive people are permitted to live, called ‘Benedites’, who follow the Catholic faith, living simple lives, homeschooling and homesteading, speaking ‘Kawarthic’ Latin. From what I could gather, they produce the food for the cities, but are also controlled, only certain of them allowed to procreate, their population kept under strict control.

The story follows Maelin, a ‘counselor’ whose task it is to enforce the various strictures imposed on the Benedites, and convince them the city ways are the best ways, including getting sterilized. Of course, there is no option to opt out, but the Lantuans would rather they go without too much fuss or resistance. (And resistance there is). As the plot unfolds, we follow the gradual awakening of Maelin’s conscience, with the revelation of her past ‘indiscretions’, and how she slowly realizes the falsity of her way of life. Maelin slowly comes to realize that there’s far more to the Benedites than meets the jaded, hedonistic agnostic eye.

It’s a slow burn, but the story grabs hold of the reader, with Peco’s strong narrative sense, a very good thing for his first novel. In his sub-creation, there is an undercurrent of morality, but one that is not over-done. Maelin’s interior journey is portrayed convincingly, by an author who knows, and lives, that of which he writes.

I will confess that the ending came a bit out of the blue, leaving a number of loose threads. I won’t give it away, but some might find it disconcerting. Not that that is necessarily a bad thing, for good literature should unsettle us, and prompt the reader to think more deeply.

And that, Gaskovski has done, and done well, while entertaining us along the way.