There is much talk of the ‘last days’, the apocalypse, the end of the world. In in the midst of the turmoil that swirls around us – but hopefully not within us – Catholics, especially on this Fatima memorial, should keep three things in mind. Well, at least these three:

First, we are always in the ‘last days’, since the first advent of Christ, ushering in the New Covenant, all of which is ‘apocalyptic’ in the sense of revealing what was hidden in the shadows and signs of the Old Covenant, and making all things new.

Second, we should keep in mind that we know neither the day nor the hour when these last days will lead to the final day, or, more to the point, the final moment, when Christ will return again in glory, like a thief in the night. Many will not expect His coming, which is why He asks us always to be prepared, our loins girded and our lamps lit. The best way to do that? By being found doing our duty, what is our task at hand – whether that be anything from the family laundry, to playing a sonata, to praying – all at the right time, in the right mode and measure.

And, finally, we should recall that any moment could be our own ‘last moment’, our personal final day, when our Lord and Saviour comes to us personally, asking for an account of our souls. If we’re doing what we’re meant to be doing, then we may hope to hear those words, ‘Well done, good and faithful servant…’, entering into a joy that never ends, and has no final day. Should we not look forward to that with anticipation? Marana tha!

Here is what Lewis says of living in the age of the atomic bomb, which we may apply, with some modification, to the age of covid, or at least our response to such:

In one way we think a great deal too much of the atomic bomb. “How are we to live in an atomic age?” I am tempted to reply: “Why, as you would have lived in the sixteenth century when the plague visited London almost every year, or as you would have lived in a Viking age when raiders from Scandinavia might land and cut your throat any night; or indeed, as you are already living in an age of cancer, an age of syphilis, an age of paralysis, an age of air raids, an age of railway accidents, an age of motor accidents.”

In other words, do not let us begin by exaggerating the novelty of our situation. Believe me, dear sir or madam, you and all whom you love were already sentenced to death before the atomic bomb was invented: and quite a high percentage of us were going to die in unpleasant ways. We had, indeed, one very great advantage over our ancestors—anesthetics; but we have that still. It is perfectly ridiculous to go about whimpering and drawing long faces because the scientists have added one more chance of painful and premature death to a world which already bristled with such chances and in which death itself was not a chance at all, but a certainty.

This is the first point to be made: and the first action to be taken is to pull ourselves together. If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things—praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts—not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs. They may break our bodies (a microbe can do that) but they need not dominate our minds.

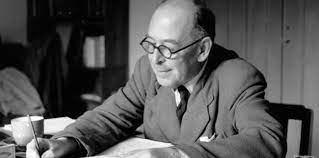

— “On Living in an Atomic Age” (1948) in Present Concerns: Journalistic Essays

These thoughts came to mind, as I listened to the words of C.S. Lewis, and his own quite-Catholic understanding of how we ponder what will one day be the World’s Last Day, or, in this case, Night: