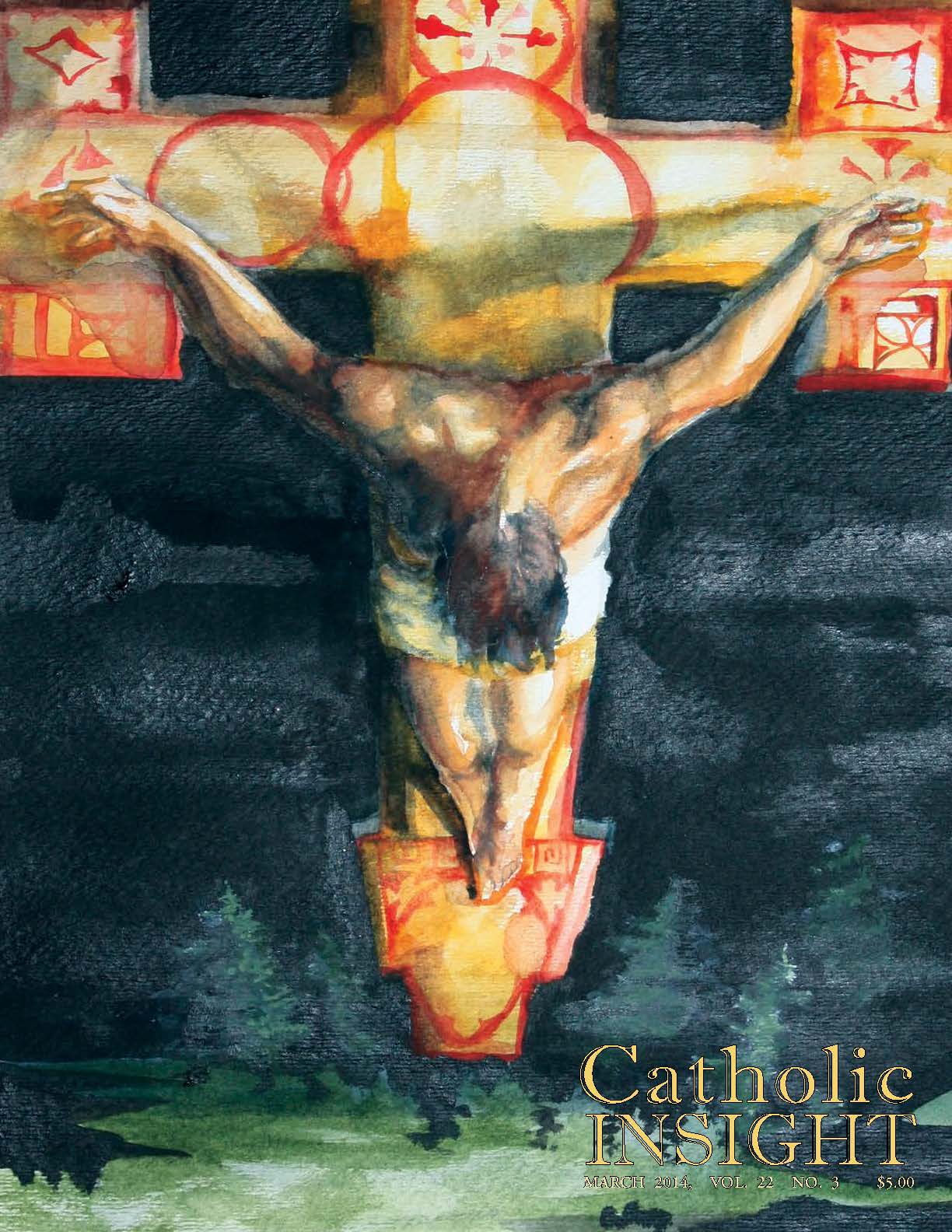

Our March 2014 cover artist, Joseph Ferrant, is the sixth of eight children. He is currently studying English and Theatre at Redeemer University and is a student at Our Lady Seat of Wisdom. He has been drawing for quite a long time, and has studied art formally at the Academy of Realist Art in Toronto.

What is this piece about?

As much as I would love to claim some sort of thematically deep ideal behind the work, it is pretty much what it looks like: a somewhat blatant rip-off of Salvador Dali’s Christ of St. John of the Cross, set on a semi-Franciscan cross in a bit of forest. The original composition of the body is a view from, supposedly, God the Father, though Dali himself took the composition from a sketch John of the Cross made after a mystical experience in which he saw the cross from that point of view. I always loved Dali’s Crucifixion, but I still wanted to make it more “my own” and I also felt that it really didn’t have the right amount of realism. Christ was, after all, suffering, being the fleshy fruit on a new tree of life, and I always found those bloodless Christs to be a sacrilege to this ancient art tradition. Still, splattering some red around and adding a crown of thorns wasn’t enough, and in my attempt to find things in the original that could be changed without changing the composition or lighting, I resorted to changing the cross. Because it was winter and because of my proximity at the time to Madonna House, I thought I would paint a Russian Orthodox cross. To my embarrassment, I mistook the cross of St. Francis for an Orthodox one and made a mix between the two. The pines are there because pines are easy to paint and they fit with the theme, though you could also see them as the darkness or wilderness of the world.

Who or what did you learn from?

Mostly I was self-taught, until I joined a craft store group and did training in folk and craft art for a couple years. After that for another decade or so, I did some beginner art classes infrequently around Ontario, while still practising on my own. I really can’t say I advanced very quickly and my interest in the process did at times wane. However, in my second year of university a friend of mine suggested a traditional art workshop or atelier in Toronto, called the Academy of Realist Art. The following summer I spent three months there, at the beginner’s level, perfecting my drawing. Arguably, I learned more in those three months than in years doing art on my own.

How would you define beauty?

After having to write three major papers on this theme (and after getting mediocre marks for all of them) I think my opinion on the matter is void. Still, to give you some idea I say: Beauty is a canonless canon. We all know it exists. We all scale things by it. But damned if we don’t know the first thing about where it starts and where it ends or why it is even present in our range of consciousness to observe. I guess that is why it is listed as a transcendental.

Still, on a particular level, researchers have found that humans tend to like things that are symmetrical and harmonious, having perfect or near perfect mathematical harmony. As this order is very much intrinsic to the fundamental building blocks of physical realty both on the cellular and atomic levels, I would argue that all of reality is beautiful. Which I think fits rather nicely with the first words of Genesis.

What is the purpose of art?

I would say the best definition for art is the one most Christian artists and theologians typically have used: that the act of creating is symbiotic to the creative nature of God and as such art is a way of recognizing or conventionalizing God. It’s also a good way to see how omnipotent a divine creator would have to be, when compared to our own endeavours. And of course, beauty, the common cause for and result of art, marks our own desires for something beyond ourselves and sets us in mind of the sublime.

In regards to my area of art (classical realism) I have found, through studying and creating it, that art works a bit like a mother bird digesting worms for its young. In its original status, visual reality is hard to take in all its forms, tones, shapes, colours, and lines. Often, most people don’t even see that reality is made up of parts; that light and colour have diminishing tonalities, depths, points, and highlights; that figures and faces are made up of geometric shapes and lines and contain symmetry and composition. So when the artist takes an image and reduces the reality of it to a flatter, less detailed “reality,” the beauty of image from reality is refreshed as it were and made digestible. Even in the case of hyper-realism, just knowing the fact that an artist, say, managed to paint all the pores in a portrait of a face, can cause a viewer to do a double-take on reality.

Who inspires you and what inspires you?

Many artists have inspired me from very early on. Though it’s somewhat sentimental, I have to say my parents always did their part in infusing a love for visual arts (as well as forking out the money for lessons and supplies and managing to not be snide when I’d triumphantly present some tortured piece of paper with scribbles on it, tempering praise with constructive criticism). To point to more exemplary art figures, I love the work of the Pre-Raphaelites, William Bouguereau, and Pietro Annigoni, as well as Caravaggio and Vermeer. Also, I grew up surrounded by the works of my godfather, Petru Botezatu, a Romanian icon painter, and much of my early attempts at painting were inspired by his work.

I am also very much inspired by nature, particularly around my home in the Ottawa Valley, and though they are somewhat apprehensive of it, my sisters have been the muses and subjects of many a portrait. Lastly, I’m inspired by my Faith and by Christ. Catholicism, more than any one source, has been a muse of the most varied and wondrous beauty. Painting this bride in all her dark brilliance has been a joy.